EGWG Writing Class #8

Revision

You’ve finished the first draft of your book. What an accomplishment!! You deserve to celebrate. So, go out to dinner with your spouse or a close friend, have your favorite meal and splurge on a dessert you’ve been craving for a while.

Then, take a break from your book. You probably need one. The break will give you a chance to rest your brain, and put some emotional distance between you and your novel. Why? Because a rejuvenated brain and some distance between you and your story will help you be more objective when you begin the revision process.

You groan and say, “Revisions? But I ran it through my critique group and a couple of friends. They caught all the typos, spelling and punctuation errors, and said it was ready to go.”

Sorry!! But your manuscript isn’t ready for an agent query, a pitch at a writer’s conference, or self-publishing yet. What’s needed next is your own self-evaluation and revision of your book. Here’s how:

- The most comprehensive and fool-proof way to self-edit your own work is to make an outline of your entire manuscript. manuscriptshredder.com says this is a one or two-line description of what happens in every scene in your story. You could do this on an excel spreadsheet or use the synopsis feature in Scrivener. (Google it under Scrivener’s Synopsis Outline). To avoid the mind- boggling attempt of looking at all the following criteria at once, make notes of necessary revisions progressively, one Evaluation Criterion at a time. Let’s get started with criterion number one, below.

Timeline:

- Maria D’Marco (reedsy) says to check the timeline of your book. It has to make sense, support the story, and have no inconsistencies. For example, if your character used a cell phone in a 1908 romantic novel or presented evidence of DNA in 1983. Your time line should also show if any scenes are missing or out of order.

Theme:

The Theme is the message you take away from the book.

- Is it what you intended?

- Is it clear enough but not too obvious?

- Is there character growth relative to the theme, where does that happen, and does it continue to grow?

Middle of the Story:

Looking at your outline as a whole, is the middle thin? If so, add more action, tension, conflict or maybe a sub-plot. In the middle could be a flashback scene that concerns character growth, the character examining a lie or working through a dark moment. Everything in the middle has to keep moving to keep the reader interested.

Scenes:

- Identify any scenes that do not move your plot forward and make a note to cut them. These could be world-building exposition and character-building scenes that don’t have a lasting effect on the plot. Make sure that when you cut the scene, you make note of any essential information you might need to add to another scene.

- Are all the scenes complete? There are two parts to a scene: action and reaction. The three action parts are goal, conflict, and disaster. The three reactive parts are reaction, dilemma, and decision. If the scene concerns a reaction, are the emotions of the main character clear and relatable?

Example:

Liz stood up to her husband. “I’ve had enough. I’m leaving. I just came for my things.”

“No, you’re not going anywhere,” said Ron. He pushed her out of his way, but she followed. He ran through the garage, grabbed a sledge-hammer, then dashed to the car and smashed all the windows with the kids in the back seat.

She tried to stop him. He slugged her, knocking out a front tooth. He stood admiring the completely gutted out windshield as the children screamed inside the car. “Try to leave now,” he said with a maniacal laughed, and went into the house.

That was her chance. She lifted each child onto a hip and ran over a mile to a friend’s house. She’d find a way to start a new life and never go back.

________________________________________________________________________

What was the goal? To get her things and leave.

Conflict: Ron tried to prevent her from leaving.

Disaster: Ron smashed all the windows in the car, so it wasn’t drivable.

Reaction: She tried to stop him.

Dilemma: She was hit, stunned, and couldn’t stop him.

Decision: She put a child on each hip and ran to safety.

- Do the scenes all end in the right place? A logical place to end a scene is just when an event is resolved and the characters have taken on a new purpose. The reader is looking forward to seeing what will happen next.

- Check the locations/settings of the scenes. You know the season, time of day, the colors and textures in your scenes, the smells, tastes, sounds, touch, sights, and placement of each character. You know how your characters look, their emotions and feelings, and how action will progress within the scene. But can your readers ‘picture’ your setting and its rich ingredients?

If not, now’s the chance to add something fresh or unexpected; instead of dinner in a restaurant, how about a moonlight dessert on the beach.

Plot:

- Identify any sub-plots that do not impact the main plot, and make a note to cut them. Again, make notes of important information to add to another scene.

- Identify plot-holes, for example:

- An all-powerful villain that’s easily defeated.

- A character’s personality changing greatly between two scenes with no explanation.

- A woman lives with her daughter and mother. She sees a crime committed and the criminals are after her. A detective gets involved and at that time, she’s concerned about her daughter and mother. Then she falls in love with the detective and there’s no mention of the daughter and mother in the rest of the story. That’s a plot-hole and a big, missed opportunity.

- A character arrives too fast from a long distance.

Characters:

- The themanuscriptshredder.com says make a character arc. A character arc is the quest and subsequent, personal change of a character as they progress through the story. The character in question should grow from one type of individual into a different one as a reaction to the obstacles presented in the narrative.

- Follow each character through the entire manuscript. See the story through the character’s eyes and add what’s missing. For example, add more description to enrich your protagonist’s experience through sight, smell, taste, touch, sound, thoughts, emotions, feelings, dialogue, interactions, actions. And ask yourself:

- Does the protagonist have a purpose? What is it?

- Are your characters believable?

- Do they contribute to every scene they’re in?

- Do their actions make sense?

- Are they cliché meaning predictable, or superficial?

- Are they critical to the story? If not, cut them out.

- Do they move the plot toward the goal?

- Will readers be able to relate to them?

- Are the character’s reactions consistent with his/her place in the character arc?

- How is the antagonist presented ? Is he just there? Make him colorful in some way. Give him a subplot and make him a rounded character.

- Look for characters who could be combined. Does your young adult heroine really need an annoying work friend and an annoying school friend? Combine them into one person. Make it easier for your readers to keep track of your secondary characters by using as few as possible.

- Make sure your secondary characters appear throughout your story. They shouldn’t be in one scene and never appear again.

Point of View (POV):

You may have already worked with Alpha readers, which could be a writing group to whom you’ve read your chapters and received feedback and corrections. Perhaps during that process, you had some Point of View errors identified, and you’ve already fixed them. So, by now, there should just be minor Point of View problems. If that is not the case, here are some general tips to help you identify problems with Point of View:

- The two most common Points of View are First and Third Person. Make sure your Point of View choice is best suited for your story. If it’s not, you’ll have to do a lot of rewriting to fix the problem.

- Look for scenes in which your POV character says or thinks something he can’t know or think through his own sight, smell, hearing, touch or taste and revise.

- Look for head-hopping, two points of view in one scene or paragraph, and revise.

- If you’ve written your story in third person, deep POV, you definitely wanted to put your reader into the head, heart and action of the character. But overuse of passive voice is death to achieving the intimacy and closeness of deep POV with your reader.

Examples:

- Her shoulder was crushed by the beam and she screamed. (This is passive voice, with shoulder as the subject and beam as the object.)

- The beam crushed her shoulder. She screamed. (The syntax is manipulated so that now the subject becomes the beam, and her shoulder is the object. The effect is that the sentence is active and sounds more immediate and personal.)

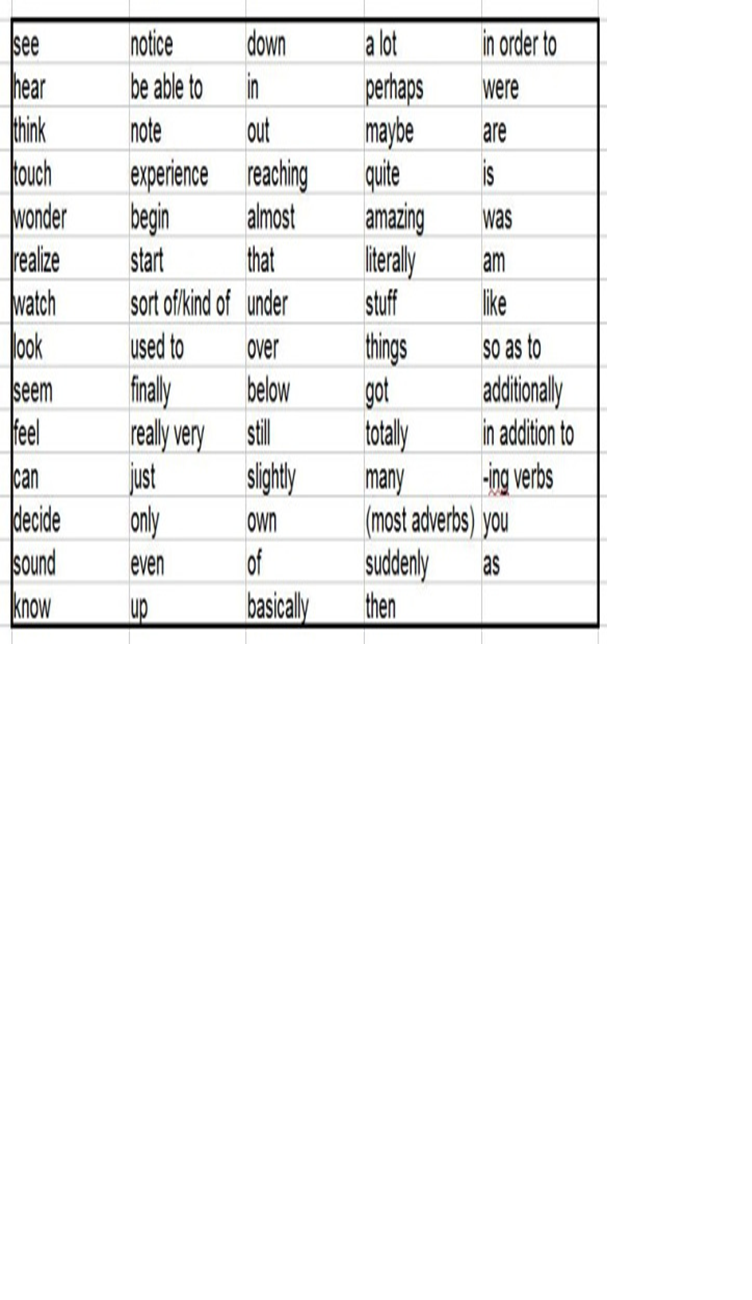

- Do a find for filter and barrier words that separate the reader from becoming one with the character and the story’s action. See page 12 for a list of filter/barrier words.

Dialogue:

Tips for reviewing the dialogue in your story:

- Does it support and move the story in accordance with the plot?

- Does the dialogue expand and deepen the understanding of the story, the characters, and the relationships between all the characters?

- Polish your dialog by cutting down on dialog tags and replacing with attributes and action beats.

- Tighten the dialog by cutting unnecessary words.

- Could you make a line memorable with foreshadowing?

- Does it promote the outcome of the scenes?

- Eliminate dialogue in your story that is an unnecessary info-dump, like back-story already mentioned in the narrative.

- Eliminate unnecessary chit-chat dialog and filler in your story. But how do you spot them? The first symptom is that the dialogue is boring. Specifically, if the dialogue is just two characters exchanging dialogue about a subject that readers either already understand or simply don’t care about–that’s a good sign it’s chit-chat.

- Fillers are personal introductions, court-room rhetoric, the Miranda rights, most political speeches, ordering at restaurants, chatting with grocery clerks–or two friends just talking about nothing over coffee. And if your readers were with your character when she got the bad news about her cancer, then they don’t need a blow-by-blow recap when she visits with friends later.

Setting:

In the first draft, according to Joanna Szabo, Editor, you may have focused on getting down the bones of the story, but in the revision stage, you need to bring your world to life.

The setting is the time and place of your book and the backdrop against which the characters act out the scenes in it. A story with a poorly portrayed setting is like a play on a bare stage.

You have character and plot (the important parts) but no sense of place. A strong setting is almost like a character in its own right. It has heart and soul, different moods, and influence on the characters and the events. Here are some important points to consider:

- If your story takes place in an exotic city, did you make that city come alive to the reader and your character’s senses?

- If you’re writing historic fiction, put your reader on the streets of 17th century Oxford or Rome in the year 200 B.C.

- If you’re writing a science fiction novel, get creative by modifying current technology to fit the distant future.

If you’re writing fantasy or building a magical system, write down all the rules of your magic, so you can catch any of your characters breaking them.

- Will your setting trigger the reader’s feelings and emotions that you wanted?

Transitions and Pacing:

Maria D’Marco says that transitions are paragraph breaks, chapter breaks, or scene changes, and they can come at the end of a paragraph, chapter, or scene. But they can also occur as anticipatory dialogue or “hint dropping.” Their purpose is to create anticipation, suspense, or interest in the reader so he turns the page and keeps reading the story.

Maria says that pacing ties to transitions, as well as to types of scenes, serves to keep readers breathless and excited or bored to tears. It is the reader engagement factor that determines the rate at which your story is absorbed. Pacing is sometimes referred to as ‘flow.’

Is the pace too slow or too fast? To speed the pacing up, use lots of dialogue with short action beats. To slow the pacing, add action beats, thoughts, description, and lengthened speeches.

To strengthen the reader’s engagement in the story, try developing a ‘log’ of the transitions in your story. That could help you identify transitions and pacing that are flat or boring. Do you have a scene or chapter that ends with the protagonist “going to sleep?” Not recommended. It may encourage the reader to “go to sleep” too.

Sentence Starts and Structures:

Maria says, everyone has writing habits. Here are some examples:

- Repetitive phrases like: He shrugged; She smiled; He stood.

- Starting a lot of sentences with a character’s name, or pronouns.

- Overuse of filter/barrier words. Refer to the list later in this article.

- Overuse of dialog tags.

- Eliminate unnecessary passive voice. Example: Passive – “A Hard Day’s Night” was written by the Beatles. Active – The Beatles wrote “A Hard Day’s Night.” The Active voice gives the reader clearer, faster, and more concise information.

If you know what your repetitive writing habits are, do a ‘find’ and revise with a better choice, or read your manuscript out loud, listening for those repetitive words.

Polish Your Chapters:

- Beginnings–Can the chapters begin further in? Does the opening grab you? Do any chapters begin the same way?

- Endings—Can you end a chapter earlier? One or two paragraphs earlier? Can you add something to the momentum? A line of moody introspection or description? A moment of decision or intention? A snappy line of dialogue? Or an outright question?

Identify 5 Big Moments In Your Manuscript:

Pick out the 5 biggest moments or plot points in your story. Go back to those moments and see if you can make them better; heighten the actions, the emotions, or increase the tension. Sit back and think about it. Rewrite it. If it works, keep it.

***

Now that you’ve completed the self-revision process, are you wondering if it’s possible you missed something? The answer is likely yes, and there’s more you can do to get your book ready for an agent query, a pitch at a writer’s conference, or self-publishing. Be patient and take the time to consider the following:

Alpha Readers:

Alpha readers can be a writing critique group, a trusted friend, or someone who loves to read. Maybe during the writing of your manuscript, you shared your story with an Alpha Reader and got feed-back and corrections.

However, Hannah Collins, of Stand Out Books, warns that it can be dangerous for a writing project if you listen to outside voices too early. The writing can take your plot or characters in directions you didn’t expect to go. There’s an organic magic to this process that external voices could disrupt. So, make sure you’ve worked out the conceptual details of your story before you share your chapters with an Alpha Reader.

The Alpha Reader usually works with you as you write each chapter of your story. It’s recommended by Hannah that you know your Alpha Reader because it gives you the ability to filter and decipher their feedback.

Another advantage with an Alpha Reader is he/she can catch mistakes before they “infect” the story in coming chapters. A good Alpha Reader will:

- Provide a respectful, collaborative relationship with you and your book.

- Find Plot holes.

- Identify issues with continuity, characters, pacing, and story structure.

- Provide constructive suggestions on word and sentence changes.

- Catch mistakes in spelling, punctuation, grammar and typos.

- Find POV errors.

- Point out repetitive words and phrases.

- Fact-check.

- Tell you if your story isn’t believable or lacks originality.

You then review all the suggested corrections and changes, decide which you will accept, and add them to your manuscript. Now you have a pristine story. Right? Maybe, but consider this.

The Beta Reader:

The best Beta Reader is a person who loves to read and reads your manuscript when it’s completely finished. For free. That’s right. You don’t pay a Beta Reader.

KM Weiland suggests that the chief advantage of using a Beta Reader is that he can read your book, and provide you with a fresh, objective viewpoint to your book, and help you understand how actual readers will react to your story. For example:

- It grabbed his attention from the first page—Or it was boring.

- The characters were authentic, and they triggered the right emotions in him. He cared what happened to them, or he didn’t like the characters.

- The description painted clear scenes and appealed to his senses, or after reading the book, he had no clue what the scenes or characters even looked like.

Where do you find Beta Readers? Most writing groups have people listed as willing to do it. Just find a friend who loves to read, or Google it on the internet, specifying your location. Here’s some local writing group resources:

- California Writers Club, [email protected]

- Northern California Publishers and Authors, [email protected]

- Elk Grove Writers Guild, [email protected]

- [email protected]

Another alternative after completion of your self-editing process is manuscript editing software programs. They can alert you to the overuse of adverbs, clichés, redundancies, overlong sentences, sticky sentences, glue words, vague and abstract words, diction and the misuse of dialog tags. Here’s a list from www.bookbaby.com, you can explore and consider.

- AutoCrit – $29.97 Mo. It can catch generic descriptions, passive voice, too many pronouns, names, and “ing” words, and too many “ly” adverbs.

- Consistency Checker—It’s free and catches inconsistent hyphenation, spelling, numerals, compound words, inconsistent abbreviations.

- Draft is a free writing, editing, collaboration, and publishing tool.

- Grammarly—Basic is $29.95 Mo. It will follow you around the Web to check blogs, Google Docs, Gmail, etc.

- Hemingway Editor—the App is free. And for $19.99 you can import and export your text to word.

- MasterWriter—9.99 a mo., $99,95 per year, or $149 for a two-year license. It’s called a Thesaurus on Steroids in the cloud that will improve your vocabulary.

- ProWritingAid–free online with premium editions at $40 a yr.

- Smart Edit—for Word is $77.00. Has unique features that detect curly/straight quotes and counts hyphens and em-dashes.

- WriteMonkey—Look it up for a price. One unique feature is you can manage separate chapter files in a book-length work using a “Jumps” feature.

Self-Editing vs Hiring a professional editor:

The benefit of self-editing, using Alpha Readers, software editing programs, a Beta Reader or two, and going over your manuscript numerous times, is to remove the obvious problems so a professional editor can focus on the entire book with a fresh perspective.

Now, it’s do or die, and you want to self-publish. But . . . what if there are still problems lurking in your manuscript? A hard truth is that you won’t find all the problems in your story, and neither will the Alpha and Beta Readers. The consensus among the writing professionals is that you need to hire a professional editor. The professional editor will take your book to the next level.

According to Rachel Deahl, book editors do a lot more than just read and edit raw manuscripts. They are a key part of the chain of command in publishing and have a lot of influence over which books get published and which ones don’t.

Types of Professional Editing:

You will need to determine which level or type of professional editing you need. Terms can be confusing because the terms are often used interchangeably within the industry.

So, when hiring a professional editor, get it in writing what his/her editing includes for the following basic types of editing:

- Copy Editing—Includes finding mechanical errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

- Line Editing—Covers line-by-line editing and analyzes each sentence for word choice, power and meaning of sentence, looks at syntax and determines if a sentence needs trimming or tightening.

- Mechanical Editing—Looks at application of style rules, (like Chicago Manual of Style and Associated Press) of capitalization, spelling, abbreviation and other style rules.

- Substantive Editing—Involves tightening and clarifying at the chapter, scene, paragraph and sentence level.

- Developmental Editing—The big picture. The developmental editor looks deep into all aspects of a manuscript, including pacing, subplots, plot, characters, point of view, tense, dialogue, setting and more. The developmental editor may suggest that the manuscript has the wrong number of chapters, or that the chapters and paragraphs are in the wrong order. He may also point out missed opportunities to bring out the theme(s) of your story, or ask you to choose a different setting or time period for your story.

As you might imagine, this type of editing is more expensive, and will require that you work closely with the editor. Here are some tips:

- Be open-minded and seriously consider the feedback you get.

- Establish good communication and flexibility between you and the editor. Discuss your vision of your book with him and come to an agreement before you proceed with him. If you can’t agree on the vision, find a new developmental editor.

- Once you are in agreement with the editor on the vision and direction of your story, stay focused on the big picture as you make any suggested changes.

- With an engaged author and editor, the final manuscript will be a source of pride for both.

What credentials does a Professional Editor have?

- College degree: Most editors have at least a bachelor’s degree, usually in English, communications, or journalism. Some have graduate degrees, but it’s not a requirement. More important than the specifics of your education are a passion for reading and an aptitude for editing.

- Experience: Internships at publishing houses and work in other media—such as newspaper or magazine editing.

A professional editor will:

- Provide an unbiased approach, with deeper insight and skill in addressing problems.

- Save Time—Especially if you’re obsessed with continually reviewing your manuscript to find more problems.

- Improve Language—to ensure consistency in tone and style, and make it more impactful.

- Eradicate Inconsistencies.

- Instill confidence that your book is the best it can be when it’s published.

Editor’s Fee: Some editors charge by the word. The estimated range is between $.01 to $.05 per word. A developmental editor could cost $.08 per word.

How to find an editor:

You can contact one of the below sources. If the top three don’t have an available Editor, they can help you find one, or try the internet:

- Northern California Publishers and Authors—[email protected]

- Elk Grove Writers Guild—[email protected]

- [email protected]

- Do an internet search for local professional editors

- Google “Professional Editor”

- com

Happy Publishing.

Please note: Filter and barrier words are usually associated with a name or pronoun, such as, he watched as she walked away. Jane noticed his red tie clashed with his dark green shirt.

LIST OF FILTER/BARRIER WORDS